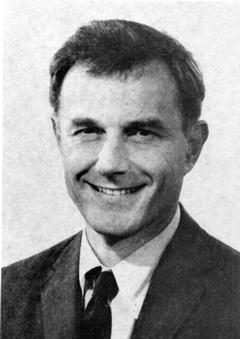

James Olds

(1922 - 1976)

Click here

Video clip (WMV; 26Mb) of an Olds' rat; a Robert Heath patient;

and a discussion of dopamine and the nucleus accumbens

James Olds, writing in Scientific American (1956, p. 107-108) ....

"With the help of Hess's technique for probing the brain and Skinner's for measuring motivation, we have been engaged in a series of experiments that began three years ago under the guidance of the psychologist D. O. Hebb at McGill University. At the beginning we planned to explore particularly the mid-brain reticular system--the sleep-control area that had been investigated by Magoun.

Just before we began our own work, H. R. Delgado, W. W. Roberts, and N. E. Miller at Yale University had undertaken a similar study. They had located an area in the lower part of the mid-line system where stimulation caused the animal to avoid the behavior that provoked the electrical stimulus. We wished to investigate positive as well as negative effects (that is, to learn whether stimulation of some areas might be sought rather than avoided by the animal). We were not at first concerned to hit very specific points in the brain, and, in fact, in our early tests the electrodes did not always go to the particular areas in the mid-line system at which they were aimed. Our lack of aim turned out to be a fortunate happening for us. In one animal the electrode missed its target and landed not in the mid-brain reticular system but in a nerve pathway from the rhinencephalon. This led to an unexpected discovery.

In the test experiment we were using, the animal was placed in a large box with corners labeled A, B, C, and D. Whenever the animal went to corner A, its brain was given a mild electric shock by the experimenter. When the test was performed on the animal with the electrode in the rhinencephalic nerve, it kept returning to corner A. After several such returns on the first day, it finally went to a different place and fell asleep. The next day, however, it seemed even more interested in corner A.

At this point we assumed that the stimulus must provoke curiosity; we did not yet think of it as a reward. Further experimentation on the same animal soon indicated, to our surprise, that its response to the stimulus was more than curiosity. On the second day, after the animal had acquired the habit of returning to corner A to be stimulated, we began trying to draw it away to corner B, giving it an electric shock whenever it took a step in that direction. Within a matter of five minutes the animal was in corner B. After this the animal could be directed to almost any spot in the box at the will of the experimenter. Every step in the right direction was paid with a small shock; on arrival at the appointed place the animal received a longer series of shocks.

Next the animal was put on a T-shaped platform and stimulated if it turned right at the crossing of the T but not if it turned left. It soon learned to turn right every time. At this point we reversed the procedure, and the animal had to turn left in order to get a shock. With some guidance from the experimenter it eventually switched from the right to the left. We followed up with a test of the animal's response when it was hungry. Food was withheld for 24 hours. Then the animal was placed in a T, both arms of which were baited with mash. The animal would receive the electric stimulus at a point halfway down the right arm. It learned to go there, and it always stopped at this point, never going to the food at all!

After confirming this powerful effect of stimulation of brain areas by experiments with a series of animals, we set out to map the places in the brain where such an effect could be obtained. We wanted to measure the strength of the effect in each place. Here Skinner's technique provided the means. By putting the animal in the "do-it-yourself" situation (i.e., pressing a lever to stimulate its own brain) we could translate the animal's strength of "desire" into response frequency, which can be seen and measured.

The first animal in the Skinner box ended all doubts in our minds that electric stimulation applied to some parts of the brain could indeed provide a reward for behavior. The test displayed the phenomenon in bold relief where anyone who wanted to look could see it. Left to itself in the apparatus, the animal (after about two to five minutes of learning) stimulated its own brain regularly about once very five seconds, taking a stimulus of a second or so every time. After thirty minutes the experimenter turned off the current, so that the animal's pressing of the lever no longer stimulated the brain. Under these conditions the animal pressed it about seven times and went to sleep. We found that the test was repeatable as often as we cared to apply it. When the current was turned on and the animal was given one shock as an hors d'ouevre it would begin stimulating its brain again. When the electricity was turned off, it would try a few times and then go to sleep. "

Refs

and further readingHOME

Pleasure

Roborats

Homeostasis

José Delgado

Robert Heath

Orgasmatrons

Hypermotivation

Superhappiness?

No More Headaches

Riley-Day syndrome

First Brain Prosthesis?

The Abolitionist Project

Utopian brain stimulation?

Electrical Brain Stimulation

Hedonism and Homeostasis

The Transcranial Magnetic Stimulator

Cyborgs, Transhumans and Neuroelectronics

Addicted brains; the chemistry of pain and pleasure

Pleasure Evoked by Electrical Stimulation of the Brain

An Information-Processing Perspective on Life in Heaven

Compulsive thalamic self-stimulation: a case study (1986)(pdf)

Video clip of rat repeatedly self-stimulating his pleasure centres

Video clip of ICSS rat repeatedly crossing strongly electrified grid

dave@bltc.com